Writing a Comic Book Script 101: Expert Storytelling Tips

- Learn essential comic book terms

- Storyboard your comic book script outline

- Write your comic book script

Think comic books and graphic novels are just for kids? Guess again. Comic book writers are some of the smartest people in the writing game, creating rich stories that readers of all ages love.

In this post, we’ll explain the writing process that goes into making comics, covering formatting, industry standard terms, self-publishing, and everything else you need to start crafting your own comic book ai script generator.

We’ve got tips for writers, letterers, and artists – whether you’re looking to create a plot first (‘Marvel style’) comic script or full script comic. Our guide’s perfect for short stories, graphic novels, webcomics, and more, taking you from your first idea right through to the final draft and finished comic.

Dive into the world of comic book creation with our detailed post on the writing process. We cover everything from industry standard terms to the intricacies of self-publishing. Essential for both writers and artists is to create storyboards with AI, which can turn your comic scripts into detailed storyboards, aiding immensely in the pre-production process of your graphic novel or webcomic.

Learn essential comic book terms

There are some crucial terms to know when script writing for comic books especially if you want to be taken seriously by the likes of Alan Moore and co. The terms below cover the most important elements of a comic book page.

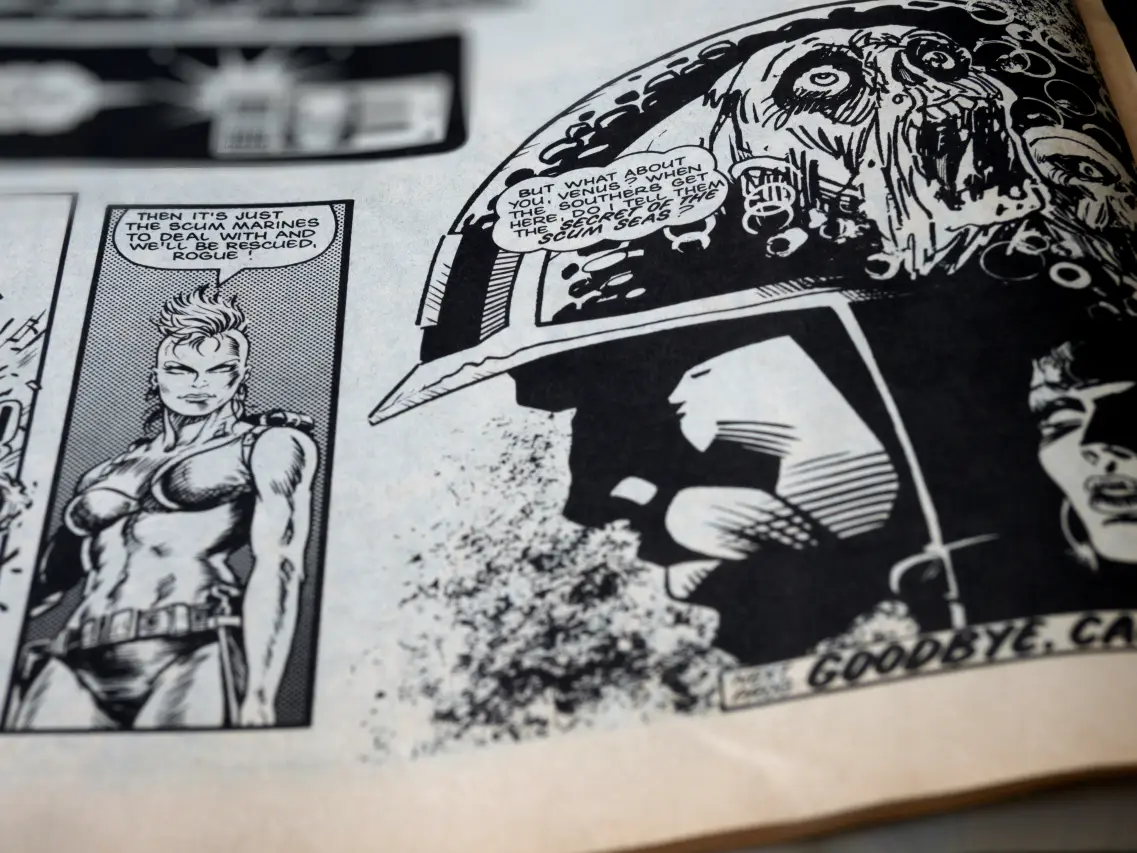

Panel

A still image in a sequence of juxtaposed images. Comic book creators can use a number of panel sizes and dimensions to mix up their formatting: square, round, triangular, narrow vertical, shallow horizontal, diagonal, and anything else you can dream up.

Some types of panels have special terms:

- An inset is a panel contained within a larger panel

- A bleed panel is where the art extends or ‘bleeds’ off the edge of the page on one or more sides

- A splash is a very large or full-page panel (sometimes called a full-page splash)

- A double-page spread is a giant splash panel covering two facing pages

While panels are usually surrounded by heavy lines called borders, parts of the art sometimes pop outside panel borders for dramatic or ironic effect. Borderless images can also qualify as panels.

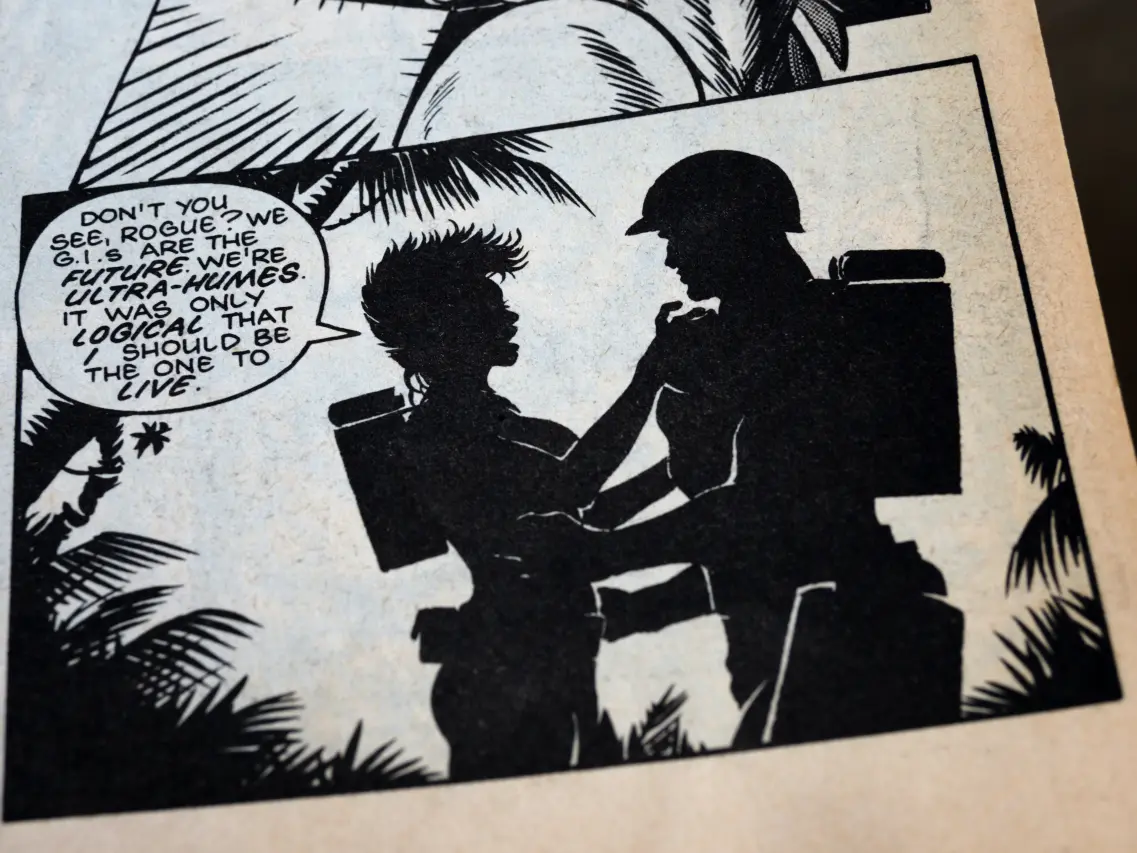

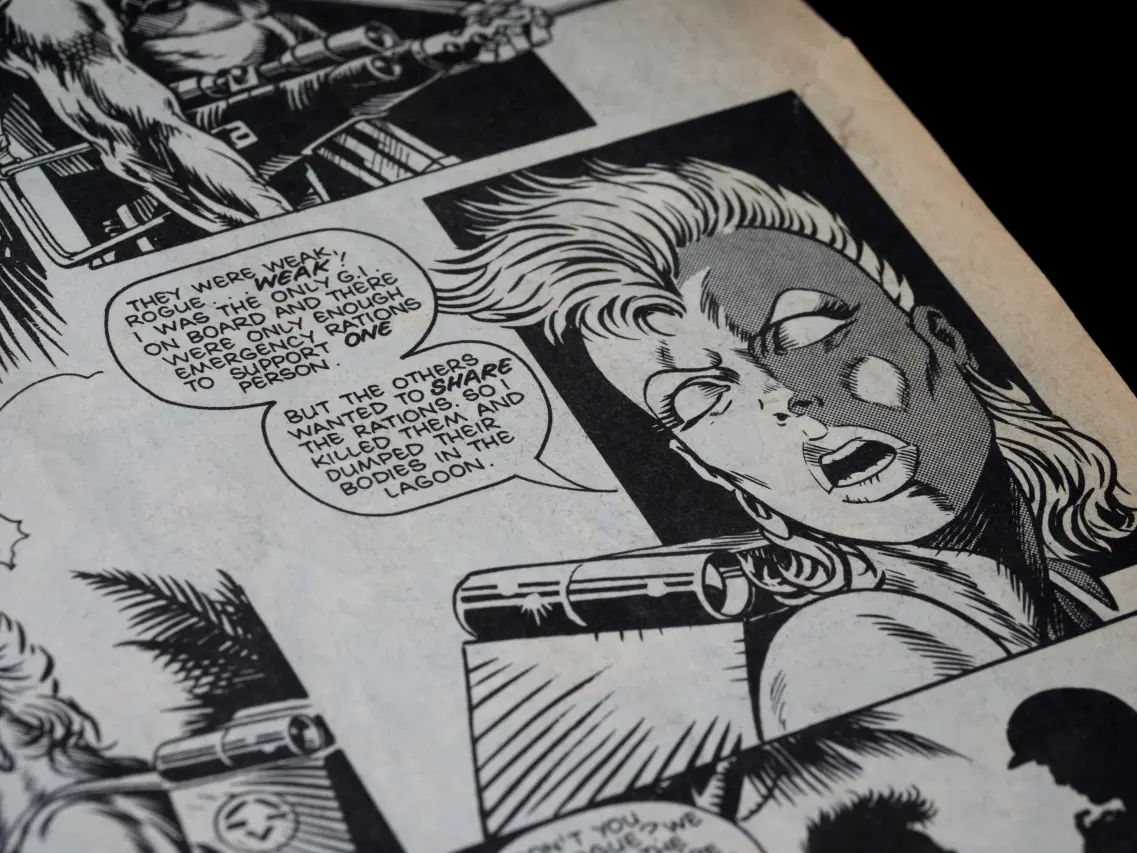

Lettering

Any text on a comic book page.

- Bold lettering is used to emphasise words

- Large lettering in dialogue represents shouting

- Small dialogue lettering usually represents whispering

Traditionally, dialogue and caption lettering was all uppercase. However, comic book writers nowadays mix things up a lot more, using upper and lowercase.

Display lettering includes sound effects and any other text that isn’t contained in a balloon or caption (like store signage, license plates, words on a computer screen, etc.).

While some comic book writers overlook them, lettering and balloon placement are vital things to get right when creating your comic book page.

Word balloon (US) / bubble (UK)

A bordered or borderless shape containing dialogue, usually with a tail that points to the speaker. Tailless balloons sometimes represent voiceover or off-panel dialogue. Like with panels, balloons come in various shapes, but ovoid is the most common when scripting.

You can use different shapes for different characters or moods. However, it’s important to use these elements consistently so that you don’t confuse your reader.

Thought balloon

A bordered or borderless shape that contains a character’s unspoken thoughts. Thought balloons almost always have bumpy, cloudlike borders and tails that look like trails of bubbles.

While thought bubbles can be useful for writing comics, it’s important not to overuse them. Like with any other form of scriptwriting, the golden rule is ‘show, don’t tell’.

Caption

A tool used for narration, transitional text (“Meanwhile...”), or off-panel dialogue. Captions usually have rectangular borders, but they can also be borderless or floating letters.

Sound effects (SFX)

Stylised lettering that represents noises within a scene. Most SFX are floating letters, and sometimes they’re an integral part of the imagery.

Again, it’s important not to overuse sound effects. Reserve them for important sounds, whether large (bombs) or small (a door gently closing).

Borders

The lines that enclose panels, balloons, and captions. You can use different styles and line weights to show different effects or moods, for example:

- Rough or jagged borders for anger or distress

- Thin, wavy borders for weakness or spookiness

- ‘Electric’ balloons and tails for radio, TV, or telephone dialogue

- Burst or double-bordered balloons for very loud shouting

- Rounded panel corners or uneven borders for flashbacks

You can also use different background colors or borders for different characters or types of dialogue.

Gutter

The space between and around panels. Although it’s usually white, you can use coloured or shaded gutters to help demonstrate mood, denote flashbacks, or just for aesthetic effect.

Get your FREE Filmmaking Storyboard Template Bundle

Plan your film with 10 professionally designed storyboard templates as ready-to-use PDFs.

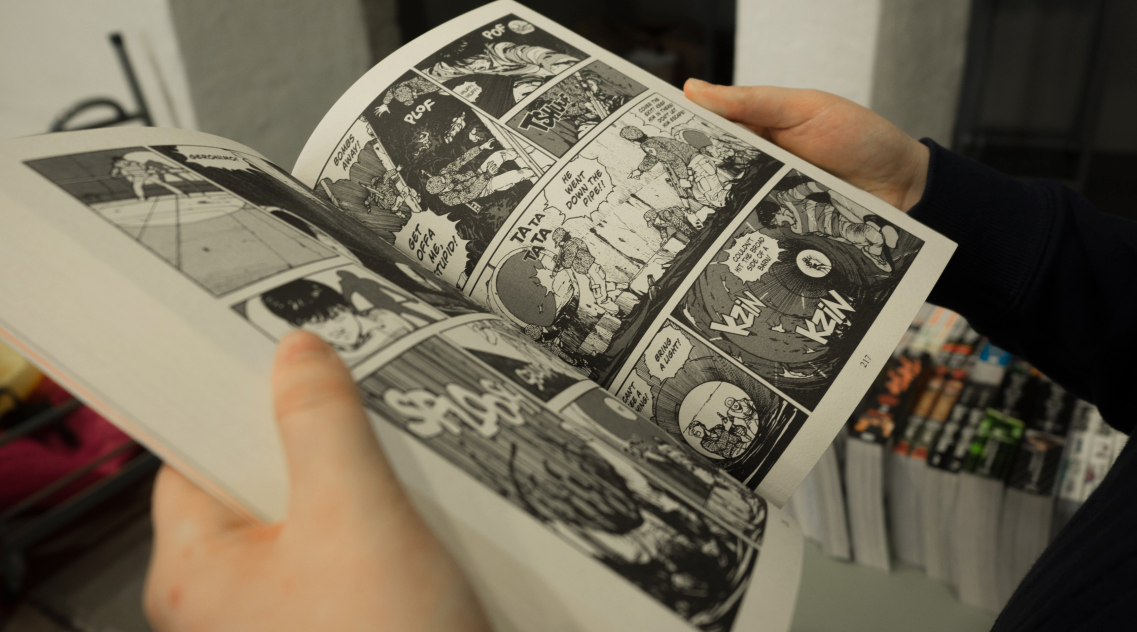

Storyboard your comic book script outline

Writing a comic book script without storyboarding the outline is like going hiking without a map. You’re going to get lost (or eaten by bears).

Storyboarding your comic book helps you nail down the storyline and key plot points, saving time, money, and stress when you start writing script pages and inking your comic panels.

Whether you’re writing a one-off indie graphic novel or an ongoing, serialised comic like Stan Lee’s Spider-Man, most comic book creators agree that you should follow a traditional three-act structure. (It’s loved by screenwriting pros around the world, so you know it works.)

- Act One: The Setup

Some people call this the ‘inciting incident’. This alliterative treat is the fancy name for the moment when the story's set in motion.

- Act Two: The Conflict

Where your characters start going through big changes (the pros call it character arc) as a result of what's happening.

- Act Three: The Climax

The resolution. Our characters confront the problem, the story comes together, and we wrap up any loose ends (a.k.a. the ‘denouement’).

The most important parts of your outline are the arcs for your main character and any secondary characters. You should map these out in as much detail as you can.

Once your outline’s starting to come together, it’s time to fire up a storyboard template with Boords. A storyboard is every comic book artist's friend. It shows you if you've missed some necessary details in the script, or if something only works in text but not visually.

Your storyboard is like a rough outline of your graphic novel, with each of the comic panels dedicated to an important moment in the story. The storyboarding process has two main goals: ensuring you have everything you need before you start script writing and lettering, and doing it in an efficient way so that you don't have to spend time fixing things afterwards in Photoshop.

Write your comic book script

Pick a script format

Unless you’ve got the whole caboodle of skills needed to create comic books – writing, drawing, lettering, and coloring – then you’re probably going to collaborate with other people to make your finished comic.

The usual way comic books come together is writing, pencilling, lettering, inking, then coloring. But this will change depending on who’s involved, how much time you have, and the publishing model.

There are two basic script formats in the comic world:

- Plot-first script (‘Marvel’ style)

- Full script

We’ll explore both below.

Plot-first script (‘Marvel style’)

The plot-first script, a.k.a. ‘Marvel’ style was made popular by the legendary Marvel Comics, largely because of Stan Lee’s relationship with artists like Jack Kirby. Even if you’re writing and drawing your own comic, this can still be a good way to go. It tends to work like this:

- The writer (or writer and artist) creates the plot and page breakdown

- The artist pencils the story

- The writer scripts the in-panel text — everything but the panel descriptions — to fit the art

The best thing about this script format is that the writer knows exactly what the art looks like, and how much room there is for text, when scripting. However, the writer gives up some control over pacing and composition, and might not get the results they want from the artist.

Full script

Full script is the most common format for comic book scripts. With full script, the writer produces a complete script with panel descriptions, which the artist then uses to pencil the story.

As a writer, you never know exactly how the artist will interpret your descriptions. However, this method gives you a bit more control over layout and pacing. The disadvantage is that you may need to trim or tweak your dialogue and captions after seeing the art.

Comic book scripts are pretty similar to screenplays in terms of script format. The tricky part is that there’s no single format that all comic book writers use.

Remember to make your script format clear and easy to follow. It should have clearly labeled page numbers and panel numbers, with indented paragraphs for all balloons, captions, sound effects, and display lettering.

Edit, edit, edit

Once you’ve got your story down, there’s going to be a lot of rewriting. Write as many drafts as you can, making tweaks and adjustments as you go. Send the script to friends for their input. Leave drafts for a couple of weeks before diving in again with fresh eyes.

Why so much rewriting? Because it’s much easier to make script writing edits at this stage than when you’re drawing the comic. If you make changes later, it’ll be costly. Remember: measure twice, cut once.

Strong comic book scripts are usually super economical in their storytelling, putting across a huge amount of information and emotion in a deceptively simple form. Here are a few tips to help you edit your script so it’s publisher-ready:

- Read dialogue aloud to hear how it flows. Does it really sound like people talking?

- Review panel descriptions without dialogue to get a feel for visual pacing and check for overcrowding

- Write a new plot outline based on your script then analyse the story structure and character arcs

Also, here are a few things to watch out for when reviewing your script:

- Too much text, visual information, or sequential action in a panel

- Too many panels on a page

- Confusing or awkward panel and scene transitions

- Giving too much, too little, or unclear direction to the artist

- Overly long speeches or internal monologues

- Redundant text that gives the same information as images in a panel

Find a publisher

If you’re thinking of going the self-publishing route (with Amazon, for example) then you can ignore this section. But if you want to get your comic published, then we’ve got some tips that'll help.

First things first, you need to identify some companies that publish the genre and format of your comic. Then decide which works you like the best, and try to make contact with the editors of those comics. See if you can find their email online, or send a quick Twitter DM asking if you can email them.

Once you’ve got an editor’s email or postal address, you can send them a proposal package. This should include:

- A cover letter explaining why you’re reaching out to this particular editor

- Plot teaser (an elevator pitch for your story)

- Approximate story length and format

- Plot outline

- Character bios

- A short description of the setting, with more detail if your story is set somewhere unusual (like a different planet, for example)

- Sample script pages or full script

- Illustrations, if possible

- Appropriate copyright and trademark notices

- Your name and contact information on every page

Your entire proposal (excluding script pages and illustrations) should be about two pages long for a short or single-issue story, or five pages for a graphic novel or multi-issue title.

If you’re sending your proposal package to a submissions editor, check the publisher’s guidelines to find out whether you should follow up on the submission. Most publishers get a lot of unsolicited submissions and don’t like to be pestered.

If you’re sending your proposal to an editor you’ve made personal contact with, wait about a month, then get in touch to see whether they’ve had a chance to look at it. You might need to do this a few times as editors can be busy. Just remember to keep it short and be polite.

Hopefully, you’ll have good news soon. We’ll all be rooting for you here at Boords!

Thanks to Anina Bennett and Chris Oatley for their helpful posts on comic book writing.