How to Storyboard a Parallel Storyline

- What’s a parallel storyline?

- Why parallel storylines are important

- Things to consider when creating a narrative structure

- Types of parallel storylines

- Parallel storyline template

- How to storyboard your parallel storyline with Boords

Every book or movie has a storyline. But some like to double (or triple) the fun by introducing an additional parallel storyline – sometimes more! These parallel universes can make your story much richer for your audience.

In this post, we’ll show you how parallel storylines work, why they’re important, and how you can storyboard a parallel storyline for your next project – whether it’s a short story, your first book, or a feature film.

We’ll even throw in some parallel storyline templates to get your next story off to a roaring start.

The Shortcut to Effective Storyboards.

Boords is an easy-to-use storyboarding tool to plan creative projects.

Get Started for FreeWhat’s a parallel storyline?

Parallel storylines – also called parallel narratives or parallel plots – are story structures where the writer incorporates two or more separate stories. They’re usually linked by a common character, event, or theme.

Playwrights and novelists have used parallel storylines for years (shout out to Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice). Recently, we’ve seen parallel storylines become popular in screenwriting, too, as Hollywood’s finest experiment with narrative form and voice.

It’s resulted in more stories that make use of parallel plots, different points of view, and extra backstory. The end result? Fruitier stories for everyone.

Why parallel storylines are important

You’re probably familiar with the typical three-act story structure. (If not, check out our handy guide: Find your perfect story structure in three acts.) It’s so common that most people think that this standard story structure is the only story structure, and that it works for every kind of story.

However, there’s a whole world of parallel narrative categories and subcategories that can help your story have even more impact. But there’s a lot to learn – parallel narrative structures can vary a lot.

- Some types of film – like The Hours or 21 Grams – have three one-act stories, with a second act so truncated that it barely exists.

- Some – like Run Lola Run – have three different versions of act 2.

- In other forms, the time jumps will be a disaster if you don't jump stories at a very specific place in the action.

In short, you can’t tell the story you want to tell unless you've got the right structure to tell it. If you stick flashbacks in at random, or start repeating the same story over and over without addressing the structure of the whole film, then your viewer won’t understand what’s happening. And that doesn’t make for an enjoyable film (unless you’re trying to bamboozle your viewer like Christopher Nolan).

Creating a narrative structure is a bit like building a house. Conventional narrative structure is a plan for one kind of building – a three bedroom house with a pitched roof. You can create lots of beautiful buildings with that design, as long as your end goal is to build a three bedroom house with a pitched roof.

But if you want to create a building with a different purpose – an apartment block, school, or laser tag arena – you'll need a completely different design (a school has totally different requirements from a laser tag arena). Lots of writers try to create parallel narratives to do this – using forms that don't suit their story, with dodgy results.

Things to consider when creating a narrative structure

Most writers don’t plan their first novel or screenplay around a narrative structure. They consider other elements first, then settle on a plot structure after answering some important questions.

What’s the character arc of your main character?

Think about the character development you want your protagonist to experience. What events will make that possible? Readers and viewers mostly care about character development, so make sure you’ve nailed that element before you get to the mechanics of how you’ll tell your story.

Is the narrator in the first person or third person?

Narrating your story in the third person will give you more flexibility. It allows you to know everything that’s happening, so you can explore parallel, circular, and nonlinear narratives. If you think your story has to be told in the first person, it’s usually safest to go with a linear story structure, with events in chronological order – but you can still use flashbacks and plenty of inner monologue.

What are the major events in the story?

Most stories follow a three-act story structure, with a setup, conflict, and climax. Each of these parts of the narrative act as touchpoints that anchor your story. Ask yourself whether they could work in a nontraditional story structure. If they could, you might want to try a nonlinear narrative. When done right, it can help your novel or script stand out.

How many points of view are featured?

Sometimes a winning story works best when told through multiple points of view. Seeing a sequence of events through the eyes of different characters creates a richer landscape for your reader or viewer. You can see this in action with Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 cult classic, Pulp Fiction, where multiple characters tell their own story – creating a series of complementary parallel storylines.

Types of parallel storylines

1. Linear narratives

Linear narratives don’t contain time jumps. They often have a large cast and multiple storylines.

1.1 - Tandem narrative

A tandem narrative is where the writer creates multiple parallel plots that are told at the same time. It’s a common storytelling form in TV that was borrowed from the stage (our pal Will Shakespeare often used three equally-weighted plots).

Tandem narrative plots can sometimes get out of hand, but writers can keep them in check in a few ways. You might want to use an overarching plot (or ‘macro plot’), which separates regular TV material (with multiple different subplots) from traditional feature film material (with a handful of parallel subplots given similar screen time).

Tandem narrative examples:

- City of Hope

- Caramel

- Lantana

- Traffic

1.2 – Multiple protagonist narrative

Multiple protagonist films are usually missions, reunions, or physical or emotional sieges. They tend to be about groups, not a main character on a single journey. Almost all films about families are multiple protagonist films, because they’re emotional sieges.

If you don’t execute it correctly, the multiple protagonist form can drift in circles, particularly in a static form like a reunion. That’s why you should think of all the protagonists as being versions of the same protagonist, and construct the film accordingly.

This could be ‘the failed boxer five years on’, or ‘the soldier at war’. There are lots of backstory problems with these films because they’re normally about unfinished business. This means you’ll need to weave lots of story strands into every scene.

Multiple protagonist narrative examples:

- American Beauty

- Little Miss Sunshine

- Saving Private Ryan

- The Full Monty

1.3 - Double journey narrative

Double journey narratives have two equally important protagonists. These protagonists journey towards, apart, or in parallel with each other – physically, emotionally or both. Because they’re often seen apart, interacting with other characters, both travellers need their own plotline. They usually have a shared plotline, too.

This is a kind of multiple protagonist form, but with specific plot content about the metaphorical double journey, so you’ll need to create three plotlines. Sometimes one character is shown in more detail than the other, with the second as more of a mystery.

Double journey narrative examples:

- Brokeback Mountain

- Finding Nemo

- The Departed

- The Lives of Others

2. Parallel narratives

Parallel narrative forms have flashbacks, time jumps, non-linearity, and fractured storylines. There are three forms, each with subcategories.

2.1 – Flashback

There are six subcategories of flashback. Some are complex, and each has a different story purpose. Sometimes, films will have several kinds of flashback throughout the story.

1. Flashback as illustration

A simple backstory device, like when a detective asks: ‘Where were you on the night of the crash?’ and we flash back to the night in question.

2. Regret flashback

Non-chronological fragments from an unsuccessful event, like a relationship.

Examples: Annie Hall, And When Did You Last See Your Father?

3. Bookend flashback

A scene or sequence in the present that appears at the start and the end of the film to bookend the story

Examples: Saving Private Ryan, Fight Club

4. Preview flashback

These stories start with a scene or sequence midway or two-thirds through, then flash back to the start, running through chronologically to the end.

Examples: Michael Clayton, Goodfellas

5. Life changing incident flashback

One life-changing moment is revealed bit by bit in one flashback shown several times.

Example: Catch 22

6. Double narrative flashback

These have stories in both the past and present. They can be put together much faster if you construct them as concentric circles, with each circle as a different story in a different time frame). You can then jump on cliffhangers in specific places in the story of the past and the story of the present.

Subcategories:

- Thwarted dream flashback: an enigmatic outsider pursues a thwarted dream.

Examples: Shine, Remains of the Day, Slumdog Millionaire

- Case history flashback: the enigmatic outsider is either dead, close to death, and their story is told by others.

Examples: Citizen Kane, The Usual Suspects, The Life of David Gale

2.2 – Consecutive stories

Consecutive stories are equally-weighted, self-contained stories that follow each other before being joined at the end. These films are split into a range of categories with different structural rules.

Some of them, like Pulp Fiction, use a ‘portmanteau’ or ‘bag’ structure – where one story contains the others, like a bag or suitcase.

Subcategories:

1. Stories walking into the picture

Stories that happen one after the other and link at the end.

Examples: The Circle, Paris, je t’aime

2. Different perspectives

Different versions or points of view of the same events.

Examples: Run Lola Run, Groundhog Day, Rashomon

3. Different consequences

Different outcomes from the same events.

Examples: Go, Atonement

4. Fractured frame / portmanteau

Fractured versions of one of the three above, using a split-up story to act like a bookend or a portmanteau.

Examples: Pulp Fiction, City of God, The Joy Luck Club

2.3 – Fractured tandem

A fractured tandem structure consists of equally-weighted stories, often in different time frames. These are fractured and truncated, then put together again in a way that steals jeopardy and suspense from the ending and creates it at the beginning and throughout.

The best thing about fractured tandem storylines is that you can use the unconventional non-linear structure to tell or fix stories that need a long set-up (like in 21 Grams, for example). This helps if each of the three protagonists is crucial to the film’s execution, but their stories are boring without hindsight – and you flash forward to give your audience that context.

Conventional screenwriting wisdom says that stories with a long set-up aren’t suitable for film. However, you can probably make it work with fractured tandem.

Examples: 21 Grams, Babel, Three Burials of Melchiades Estrada, The Hours, Crash

Subcategories:

Unexpected, often tragic, connections between apparently disparate people, triggered by an accident or random event.

Several equally important stories, some or all fractured, running simultaneously. Sometimes in the same time frame, but often in several.

Chain reactions linked to one event

Parallel storyline template

How to storyboard your parallel storyline with Boords

At Boords, we think that the best way to storyboard parallel plots is with… well, Boords. It’s the easiest way to create and share storyboards online, helping you go from idea to storyboard in seconds.

Here’s a simple step-by-step guide to start storyboarding your parallel storyline with Boords.

- Go to your project dashboard and click

New projectto create a project. Name it after your story.

- When you get the option to start with images or blank frames, pick

Add Frames– unless you already have images ready.

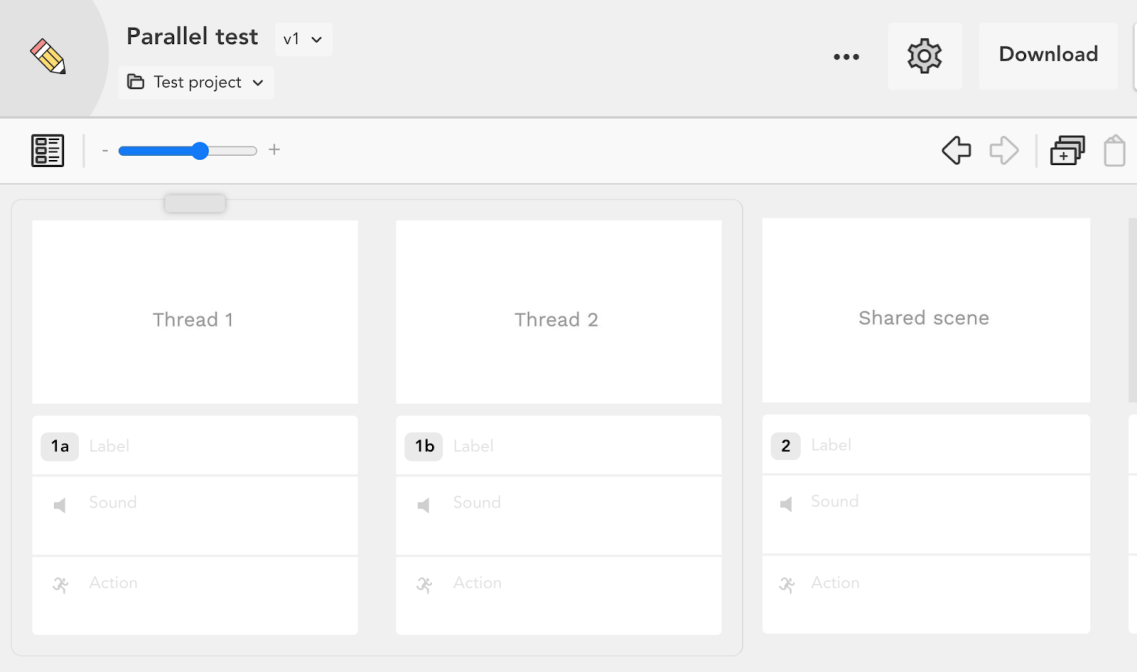

- To create two storylines side by side, click on two frames then press cmd + g to group them. (For example, if you do this with frames 1 and 2, they’ll become 1a and 1b, like in the image above.)

- Continue this throughout the storyboarding process to create a mix of threads (parallel storylines) and shared scenes (which relate to all the parallel storylines).

Get your FREE Filmmaking Storyboard Template Bundle

Plan your film with 10 professionally designed storyboard templates as ready-to-use PDFs.

Try Boords for free

Ready to take your parallel narratives to a whole new level? Try Boords for free today. It’s the simplest, most powerful way to juggle multiple storylines like a pro.