How to Write a Script (Step-by-Step Guide)

So you want to write a film script (or, as some people call it, a screenplay – they're two words that mean basically the same thing). We're here to help with this simple step-by-step script writing guide.

Or better yet, use our AI script writing generator -- it's designed to take your idea and flesh out a film script with voiceovers and camera directions for your storyboard. Bring your vision to life.

Lay the groundwork

1. Know what a script is

If this is your first time creating movie magic, you might be wondering what a script actually is. Well, it can be an original story, straight from your brain. Or it can be based on a true story, or something that someone else wrote – like a novel, theatre production, or newspaper article.

A movie script details all the parts – audio, visual, behaviour, dialogue – that you need to tell a visual story, in a movie or on TV. It's usually a team effort, going through oodles of revisions and rewrites, not to mention being nipped ‘n' tucked by directors, actors, and those in production jobs. But it'll generally start with the hard work and brainpower of one person – in this case, you.

Because films and TV shows are audiovisual mediums, budding scriptwriters need to include all the audio (heard) and visual (seen) parts of a story. Your job is to translate pictures and sounds into words. Importantly, you need to show the audience what's happening, not tell them. If you nail that, you'll be well on your way to taking your feature film to Hollywood.

2. Read some scripts

The first step to stellar screenwriting is to read some great scripts – as many as you can stomach. It’s an especially good idea to read some in the genre that your script is going to be in, so you can get the lay of the land. If you’re writing a comedy, try searching for ‘50 best comedy scripts’ and starting from there. Lots of scripts are available for free online.

3. Read some scriptwriting books

It's also helpful to read books that go into the craft of writing a script. There are tonnes out there, but we've listed a few corkers below to get you started.

- Your Screenplay Sucks! – William M. Akers

- The Coffee Break Screenwriter – Pilar Alessandra

- The 21st Century Screenplay – Linda Aronson

- The Nutshell Technique – Jill Chamberlain

- The Art of Dramatic Writing – Lajos Egri

- Screenplay – Syd Field

- The Sequence Approach – Paul Joseph Gulino

- Writing Screenplays That Sell – Michael Hague

- Getting It Write – Lee Jessup

- Story – Robert McKee

- My Story Can Beat Up Your Story – Jeffrey Alan Schechter

- Making a Good Script Great – Linda Seger

- Save the Cat – Blake Snyder

4. Watch some great films

A quick way to get in the scriptwriting zone is to rewatch your favourite films and figure out why you like them so much. Make notes about why you love certain scenes and bits of dialogue. Examine why you're drawn to certain characters. If you're stuck for ideas of films to watch, check out some ‘best movies of all time' lists and work through those instead.

Flesh out the story

5. Write a logline (a.k.a. brief summary)

You're likely to be pretty jazzed about writing your script after watching all those cinematic classics. But before you dive into writing the script, we've got a little more work to do.

First up, you need to write a ‘logline'. It's got nothing to do with trees. Instead, it's a tiny summary of your story – usually one sentence – that describes your protagonist (hero) and their goal, as well as your antagonist (villain) and their conflict. Your logline should set out the basic idea of your story and its general theme. It's a chance to tell people what the story's about, what style it's in, and the feeling it creates for the viewer.

6. Write a treatment (a.k.a. longer summary)

Once your logline's in the bag, it's time to write your treatment. It's a slightly beefier summary that includes your script's title, the logline, a list of your main characters, and a mini synopsis. A treatment is a useful thing to show to producers – they might read it to decide whether they want to invest time in reading your entire script. Most importantly, your treatment needs to include your name and contact details.

Your synopsis should give a good picture of your story, including the important ‘beats' (events) and plot twists. It should also introduce your characters and the general vibe of the story. Anyone who reads it (hopefully a hotshot producer) should learn enough that they start to feel a connection with your characters, and want to see what happens to them.

This stage of the writing process is a chance to look at your entire story and get a feel for how it reads when it's written down. You'll probably see some parts that work, and some parts that need a little tweaking before you start writing the finer details of each scene.

7. Develop your characters

What's the central question of your story? What's it all about? Character development means taking your characters on a transformational journey so that they can answer this question. You might find it helpful to complete a character profile worksheet when you're starting to flesh out your characters (you can find these for free online). Whoever your characters are, the most important thing is that your audience wants to get to know them, and can empathise with them. Even the villain!

8. Write your plot

By this point, you should have a pretty clear idea of what your story's about. The next step is breaking the story down into all the small pieces and inciting incidents that make up the plot – which some people call a 'beat sheet'. There are lots of different ways to do this. Some people use flashcards. Some use a notebook. Others might use a digital tool, like Trello, Google Docs, Notion, etc.

It doesn't really matter which tool you use. The most important thing is to divide the plot into scenes, then bulk out each scene with extra details – things like story beats (events that happen) and information about specific characters or plot points.

While it's tempting to dive right into writing the script, it's a good idea to spend a good portion of time sketching out the plot first. The more detail you can add here, the less time you'll waste later. While you're writing, remember that story is driven by tension – building it, then releasing it. This tension means your hero has to change in order to triumph against conflict.

Write the Script

9. Know the basics

Before you start cooking up the first draft of your script, it's good to know how to do the basics. Put simply, your script should be a printed document that's:

- 90-120 pages long

- Written in 12-point Courier font

- Printed on 8.5" x 11", white, three-hole-punched paper

Font fans might balk at using Courier over their beloved Futura or Comic Sans. However, it's a non-negotiable when you write a script. The film industry's love of Courier isn't purely stylistic – it's functional, too. One script page in 12-point Courier is roughly one minute of screen time.

That's why the page count for an average screenplay should be between 90 and 120 pages, although it's worth noting that this differs a bit by genre. Comedies are usually shorter (90 pages / 1.5 hours), while dramas can be a little longer (120 pages / 2 hours). A short film will be shorter still. Obviously.

10. Write the first page

Using script formatting programmes means you no longer need to know the industry standard when it comes to margins and indents. That said, it’s good to know how to set up your script in the right way.

- The top, bottom and right margins of a screenplay are 1"

- The left margin is 1.5" (the extra half-inch of white space on the left of a script page lets you bind your script with brads, but still makes the document feel balanced in terms of the amount of text on the page)

- The entire document should be single-spaced

- The first item on the first page should be the words ‘FADE IN:’

- The first page is never numbered

- The other page numbers go in the upper right-hand corner, 0.5" from the top of the page, flush right to the margin

11. Format your script

Here’s a big ol’ list of items that you’ll need in your script, and how to indent them properly. Your script-writing software will handle this for you, but learning’s fun, right?

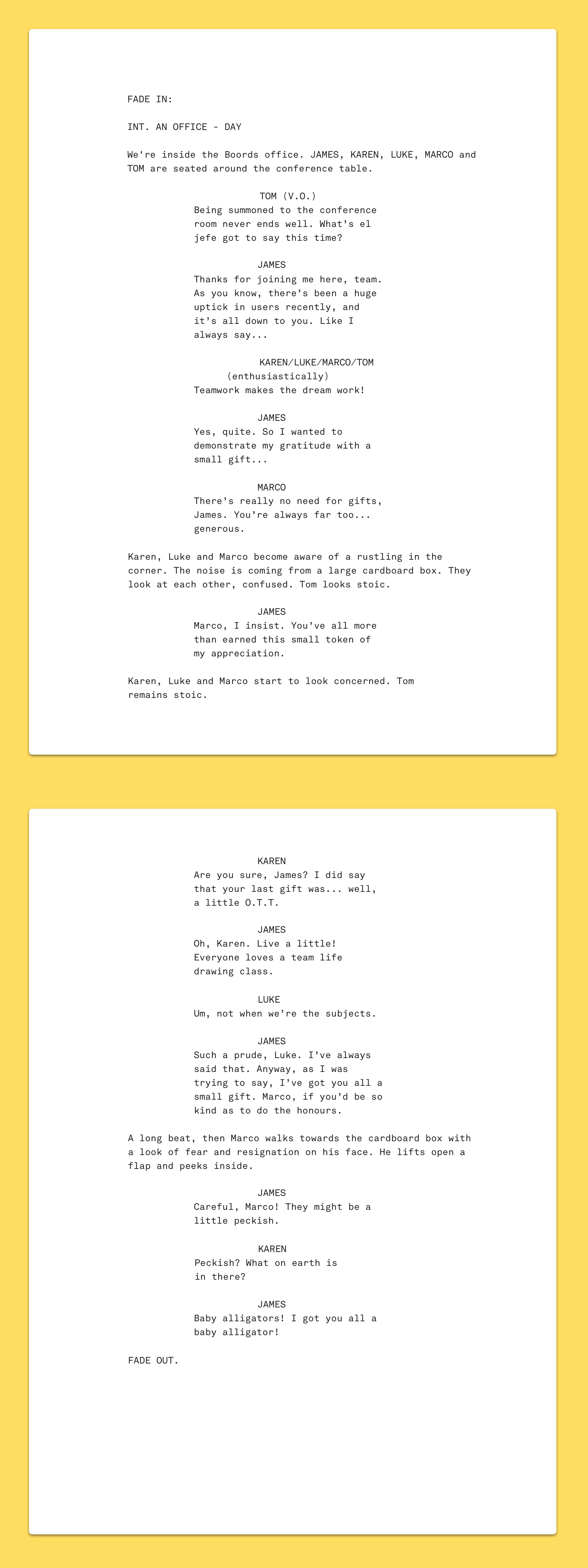

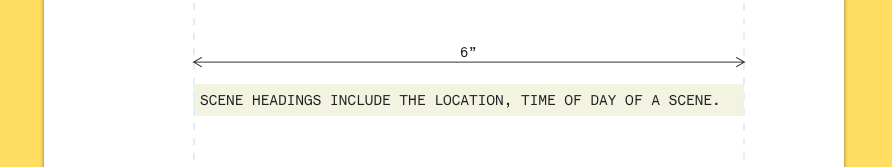

Scene heading

The scene heading is where you include a one-line description of the location and time of day of a scene. This is also called a ‘slugline’. It should always be in caps.

Example: ‘EXT. BAKERY - NIGHT’ tells you that the action happens outside the bakery during the nighttime.

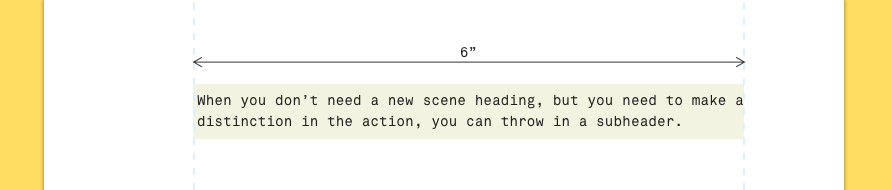

Subheader

When you don’t need a new scene heading, but you need to make a distinction in the action, you can throw in a subheader. Go easy on them, though – Hollywood buffs frown on a script that’s packed with subheaders. One reason you might use them is to make a number of quick cuts between two locations. Here, you would write ‘INTERCUT’ and the scene locations.

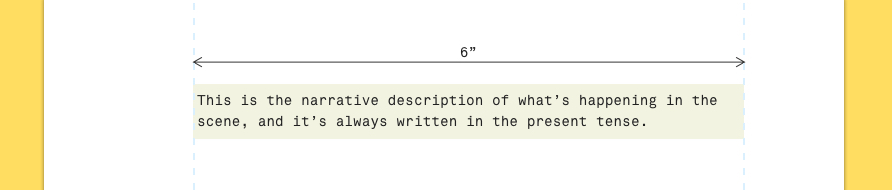

Action

This is the narrative description of what’s happening in the scene, and it’s always written in the present tense. You can also call this direction, visual exposition, blackstuff, description, or scene direction. Remember to only include things that your audience can see or hear.

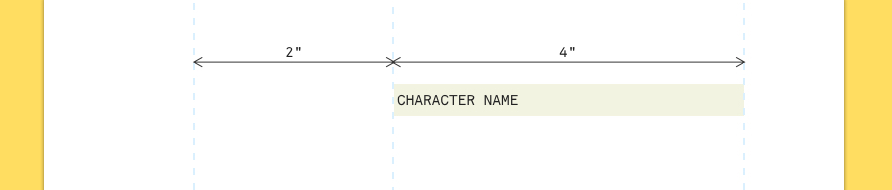

Character

When you introduce a character, you should capitalise their name in the action. For example: ‘The car speeds up and out steps GEORGIA, a muscular woman in her mid-fifties with nerves of steel.’

You should always write each character’s name in caps, and put it about their dialogue. You can include minor characters without names, like ‘BUTCHER’ or ‘LAWYER.’

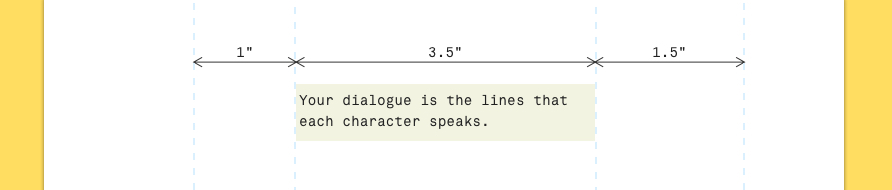

Dialogue

Your dialogue is the lines that each character speaks. Use dialogue formatting whenever your audience can hear a character speaking, including off-screen speech or voiceovers.

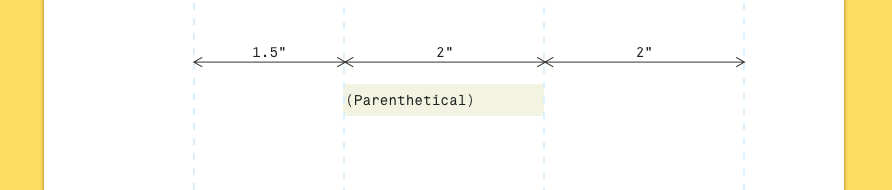

Parenthetical

A long word with a simple meaning, a parenthetical is where you give a character direction that relates to their attitude or action – how they do something, or what they do. However, parentheticals have their roots in old school playwriting, and you should only use them when you absolutely need to.

Why? Because if you need a parenthetical to explain what’s going on, your script might just need a rewrite. Also, it’s the director’s job to tell an actor how to give a line – and they might not appreciate your abundance of parentheticals.

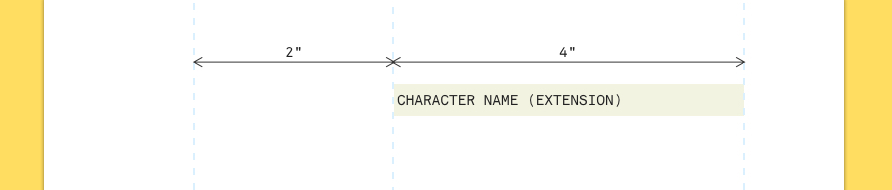

Extension

This is a shortened technical note that you put after a character’s name to show how their voice will be heard onscreen. For example: if your character is speaking as a voiceover, it would appear as ‘DAVID (V.O.)’.

Transition

Transitions are film editing instructions that usually only appear in a shooting script. Things like:

- CUT TO:

- DISSOLVE TO:

- SMASH CUT:

- QUICK CUT:

- FADE TO:

If you’re writing a spec script, you should steer clear of using a transition unless there’s no other way to describe what’s happening in the story. For example, you might use ‘DISSOLVE TO:’ to show that a large portion of time has passed.

Shot

A shot tells the reader that the focal point in a scene has changed. Again, it’s not something you should use very often as a spec screenwriter. It’s the director’s job! Some examples:

- ANGLE ON --

- EXTREME CLOSE UP --

- PAN TO --

- DAVE’S POV --

12. Spec scripts vs. shooting scripts

A ‘spec script' is another way of saying ‘speculative screenplay.' It's a script that you're writing in hopes of selling it to someone. The film world is a wildly competitive marketplace, which is why you need to stick to the scriptwriting rules that we talk about in this post. You don't want to annoy Spielberg and co.

Once someone buys your script, it's now a ‘shooting script' or a ‘production script.' This version of your script is written specifically to produce a film. Because of that, it'll include lots more technical instructions: editing notes, shots, cuts, and more. These instructions help the production assistants and director to work out which scenes to shoot in which order, making the best use of resources like the stage, cast, and location.

Don't include any elements from a shooting script in your spec script, like camera angles or editing transitions. It's tempting to do this – naturally, you have opinions about how the story should look – but it's a strict no-no. If you want to have your way with that stuff, then try the independent filmmaker route. If you want to sell your script, stick to the rules.

13. Choose your weapon

While writing a big-screen smash is hard work, it's a heck of a lot easier nowadays thanks to a smorgasbord of affordable screenwriting software. These programmes handle the script format (margins, spacing, etc.) so that you can get down to telling a great story. Here are a few programmes to check out:

There are also a tonne of outlining and development programmes. These make it easier to collect your thoughts and storytelling ideas together before you put pen to paper. Take a peek at these:

14. Make a plan

When you're approaching a chunky project, it's always good to set a deadline so you've got a clear goal to reach. You probably want to allow 8-12 weeks to write a script – this is the amount of time that the industry would usually give a writer to work on a script. Be sure to put the deadline somewhere you'll see it: on your calendar, or your phone, or tattooed on your hand.

For your first draft, concentrate on getting words on the page. Don't be too critical – just write whatever comes into your head, and follow your outline. If you can crank out 1-2 pages per day, you'll have your first draft within two or three months. Easy!

Some people find it helpful to write at the same time each day. Some people write first thing. Some people write late at night. Some people have no routine whatsoever. Find a routine (or lack thereof) that works for you, and stick to it. You got this.

15. Read it out loud

One surefire way to see if your dialogue sounds natural is to read it out loud. While you're writing dialogue, speak it through at the same time. If it doesn't flow, or it feels a little stilted, you'll need to make some tweaks. Highlight the phrases that need work then come back to them later when you're editing.

16. Take a break

When your draft's finished, you might think it's the greatest thing ever written – or you might think it's pure dross. The reality is probably somewhere in the middle. When you're deep inside a creative project, it's hard to see the forest for the trees.

That's why it's important to take a decent break between writing and editing. Look at something else for a few weeks. Read a book. Watch TV. Then, when you come back to edit your script, you'll be able to see it with fresh eyes.

17. Make notes

After you've taken a good break, read your whole script and take notes on the bits that don't make sense or sound a little weird. Are there sections where the story's confusing? Are the characters doing things that don't push the story along? Find those bits and make liberal use of a red pen. Like we mentioned before, this is a good time to read the script out loud – adding accents and performing lines in a way that's true to your vision for the story.

18. Share with a friend

As you work towards a final version of your script, you might want to share it with some people to get their feedback. The Commenting & Feedback feature in Boords allows users to directly comment on individual frames and include necessary reference links, simplifying the process of responding to client feedback.

Friends and family members are a good first port of call, or other writers if you know any. Ask them to give feedback on any parts you're concerned about, and see if there's anything that didn't make sense to them.

The Shortcut to Effective Storyboards.

Boords is an easy-to-use storyboarding tool to plan creative projects.

Get Started for FreeWrap things up

19. Write final draft

After you've made notes and gathered feedback, it's time to climb back into the weeds and work towards your final draft. Keep making edits until you're happy. If you need to make changes to the story or characters, do those first as they might help fix larger problems in the script.

Create each new draft in a new document so you can transfer parts you like from old scripts into the new one. Drill into the details, but don't get so bogged down in small things that you can't finish a draft. And, before you start sharing it with the world, be sure to do a serious spelling and grammar check using a tool like Grammarly.

20. Presentation and binding

There are rules for everything when writing a script. Even how you bind the thing. Buckle up!

- The first page is the title page, which should be written in – you guessed it! – 12-point Courier font

- The title page must include the title of your script, with ‘written by’ and your name in the middle of the page

- Put your contact information in the lower left-hand or right-hand corner

- You can also put Registered, WGA or a copyright notification in the lower left-hand or right-hand corner, but this is entirely optional

- Remember: no graphics, no pictures, no funny business

This is a list of stuff you’ll need to prepare your script before sending it out and taking over the world:

- Script covers (either linen or standard card stock)

- Three-hole-punched paper

- Screenplay brass fasteners (a.k.a. brads). Acco number 5, size 1 1/4-inch, for scripts up to 120 pages. Acco number 6, size 2-inch, for larger scripts

- Script binding mallet (optional)

- Screenplay brass washers

- Script mailers

And this is how to bind your script:

- Print your title page and script on bright white three-hole-punched paper

- Insert the title page and script into the script cover. The front and back covers should be blank – they’re just there to protect the script

- Insert two brass fasteners in the first and third holes. Leave the middle hole empty

- Turn the script over, and slide the brass washers over the arms of the fasteners. Spread the arms of the fasteners flat against the script. (Optional: use a script binding mallet for an extra-tasty fit)

- Use script mailers to send your film script out to Hollywood bigwigs

- Achieve fame and fortune. Thank Boords in your Oscars acceptance speech

The Shortcut to Effective Storyboards.

Boords is an easy-to-use storyboarding tool to plan creative projects.

Get Started for Free